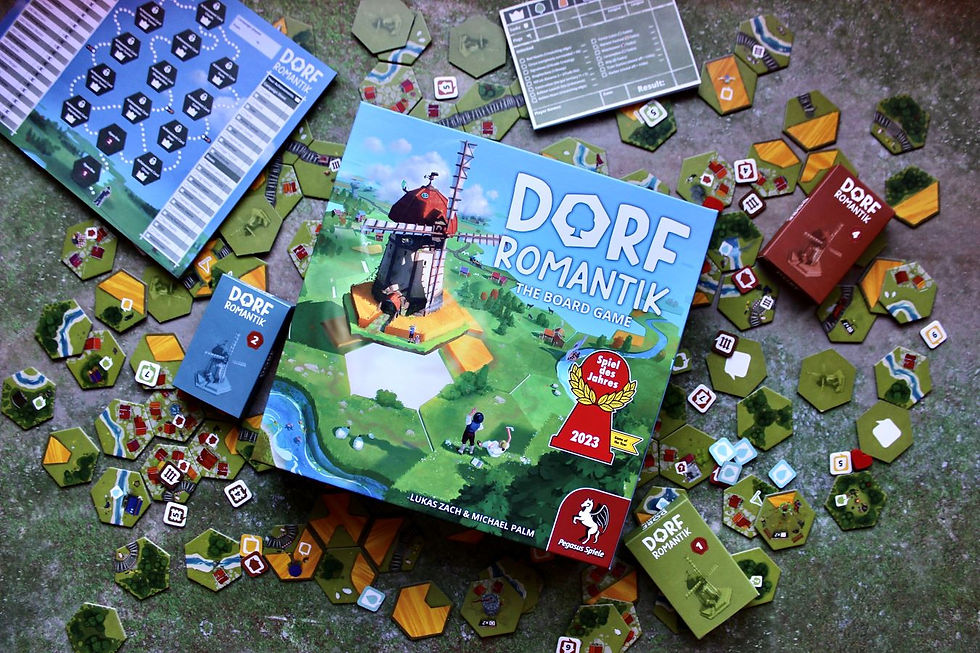

Designer: Michael Palm and Lukas Zach

Artist: Paul Riebe

Publisher: Pegasus Spiele

Player Count: 1 to 6 Players

Play Time: 30 to 60 minutes

Create a sprawling landscape—streams, rails, forests, farms, and villages—while solving an expanding puzzle. Dorfromantik: The Board Game is the 2023 Spiel Des Jahres award winning tile placement game, noted for its tranquil gameplay and inventive campaign mode.

Key Points

2023 Spiel Des Jahres (Game of the Year) winner

Based on the eponymous peaceful video game

No gameplay modifications for solo play

Campaign-style, with unlockable achievements and changing objectives

Dorfromantik: the Board Game is a tile laying puzzle game where up to six players work together to create an expanding landscape while completing as many scoring objectives as possible. The game can be enjoyed a la carte right out of the box, or played over multiple sessions in a campaign. In the latter, the player can track their progress on a campaign sheet, unlocking new achievements and adding additional components to the game.

The board game is based on the eponymous video game from a few years earlier and gameplay is mostly consistent with what you will find in the PC version—save for one rule which is the subject of some contest. Dorfromantik won the 2023 Spiel Des Jahres in a strong pool of contenders including Matthew Dunstan’s Next Station London and Jules Messaud’s Akropolis.

A Tranquil Tile Placement Puzzle

In Dorfromantik, players work together to create a vast province of different terrains—forests, farms, and villages as well as the railways and streams that intersperse them. Each turn, the player will select either a facedown hexagonal task or landscape tile and place it into the play area adjacent to a tile that has already been placed. Each tile features a different arrangement of the five terrain types and as the game progresses and more tiles are added to the play area, a burgeoning landscape of the player’s creation begins to emerge.

Although this might be a tile laying game, Dorfromantik is about scoring points. The game features an elaborate beat-your-score table, and progression through the campaign is largely advanced by scoring more and more points. Points are scored by completing tasks—laying tiles in a way that creates terrain areas consisting of a number of adjacent tiles matching the type and size of the active task marker. There should always be three active tasks, so when one is completed (or failed), the next tile drawn needs to be a task tile with a new terrain objective. The player also scores points by creating long streams and railroads, and establishing large terrain areas connected to flags of that terrain type.

And tiles can’t just be placed willy-nilly. Unlike some similar tile placement games like Carcassonne, terrain edges on adjacent tiles do not need to match; only railway and stream edges must connect. Also, the player cannot place a new task tile so that it would immediately fail the specified task (placing a railroad task tile with task marker 4 so that it is connected to a railway that is already 4 or more tiles). This is the only major rule change from the video game and was implemented to prevent players from being able to speedrun achievements in campaign mode. The game ends when there are no more landscape tiles from which to draw.

The Spiel Des Jahres nominating committee noted that Dorfromantik “takes the pressure out of everyday life. This co-operative, feel-good game presents new and exciting goals each time you play but there’s no danger of losing.” In other words, it’s lightweight, low-overhead, and casual. It’s a kickback and relaxed kind of game, comparable to other enjoyable titles like Beacon Patrol or Cascadia. And let me be clear: I love games like this. Simple rules with strategic puzzle depth is a notable design achievement. But straight out of the box, the puzzle complexity of Dorfromantik isn’t much to write home about, becoming rote and predictable after just a few plays.

Dorfromantik Campaign: A Game That Grows With The Player

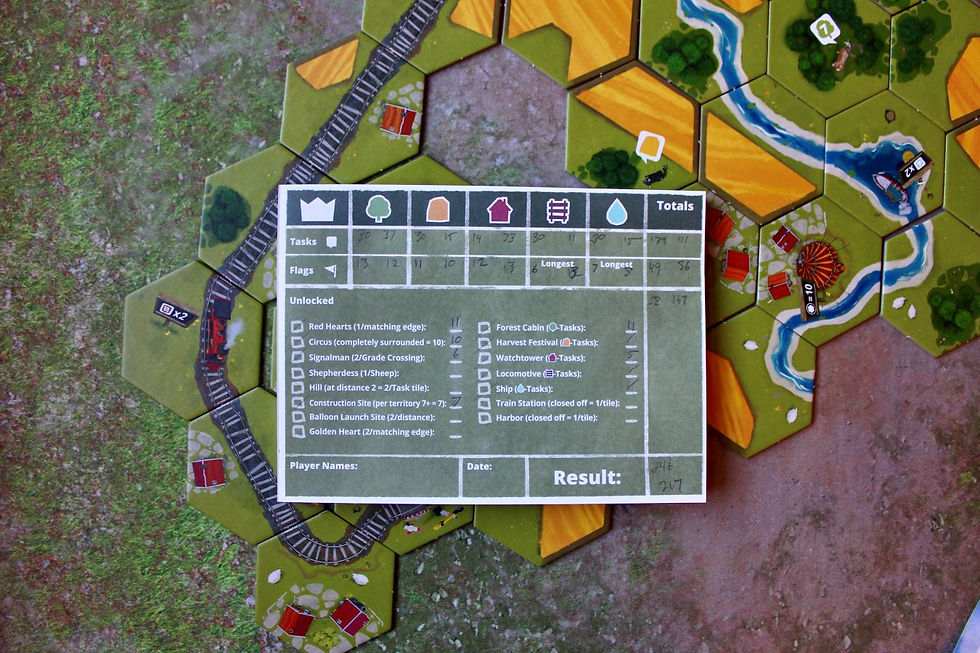

But Dorfromantik isn’t meant to just be played right out of the box. This otherwise straightforward game is equipped with an expansive campaign of challenges, achievements, and unlockable content. Campaign play is recorded on a campaign sheet, featuring one column for recording scores from game to game and two columns for tracking achievements.

Very basically, the more you score each game, the more you can progress in the campaign. At certain milestones, the player is instructed to open one of the five campaign boxes contained inside the main box and add new achievements, or scoring objectives to the game. Completing these achievements allows the player to add new components—usually additional tiles—from the campaign boxes.

The campaign mode is a slow burn, with the campaign sheet and method of progressing through it designed to keep a neutral pace for the player. It’s both difficult to unlock too much too quickly and to get too hung up on one achievement. This gradual addition of new components makes learning the game a digestible process, rather than being overwhelming and confusing at any one stage in the campaign. In this way Dorfromantik is a game that grows along with the player.

The campaign components that are added don’t really change the rules of the game; it’s still as simple as picking up a tile and placing it down. Instead, each unlockable achievement establishes new point scoring mechanisms that need to be tallied at the end of the game. So generally, the deeper a player is into the campaign, the more unlocked achievements they will have active, and so the more points they can score, all the way up to the elusive 400 point mark. While the added campaign bits don’t fundamentally alter gameplay, the player has a lot more to consider when determining the optimal location to place each tile.

Dorfromantik Campaign: An Identity Crisis?

And that overhead catches up suddenly. Over the course of the campaign, Dorfromantik can quickly transform from a pleasant 30 minute casual exercise into a taxing brain-busting enigma. When I have three dozen or so active achievements that I need to keep track of, it can feel like every time I grab a new tile, I need to cross check all of my scoring reference cards and second guess which scoring objective the tile may best accomplish. What was once a relaxing game is now a vexatious affair.

And that’s not necessarily a knock. Like a lot of gamers, I’m motivated by challenging puzzles. But late-campaign Dorfromantik is a far cry from the sleepy game that the Spiel Des Jahres committee said “takes the pressure out of everyday life.” Because I definitely feel the pressure when I’m down to three landscape tiles left in the stack, four tasks to complete, and I still need to close off my railroad. The game’s low-stakes casual promise at the outset belies how tough the puzzle challenge of attaining 400 points really is. So is this a game that grows with the player, or one that has a bit of an identity crisis? A cozy game, or a head-scratcher?

Scoring consistently-well also feels fickle further into the campaign. With more special landscape tiles added into the stacks, the randomness of the tile pull seems more impactful, as each needs to fit juuust right to score perfectly. The ideal tile for a spot will also never come along, and there are certain board states where nothing fits right. Sometimes after a bad start, I was tempted to scrap the playthrough midway and just start again, realizing that if I didn’t set up perfect tile arrangements that I wasn’t going to score high enough by the end of the game. I’ve gotten so close, but that 400 score seems just out of reach, and that plateau is frustrating. Perhaps that ceiling isn't felt as much at higher player counts with more eyes on the board.

Patience, however, may be bitter, but its fruit is sweet. And Dorfromantik is a game best played slowly and with a peaceful mind.

Final Thoughts

Who doesn’t love opening a new board game for the first time? Peeling off the cellophane. The smell of the fresh plastic and cardboard. The thrill of punching all the tokens, and opening all the sealed packets. Dorfromantik invites the player to embark on a campaign with the prospect of experiencing this feeling time and time again, each time they need to pry open a campaign box and add another unique tile with its own form and function to the game.

Progression in the campaign is one big twist on beat-your-own-score style games. Game after game, the player is more likely to beat their score than the last because of the added components and new unlocked achievements to score. This can make it tough to tell whether the player is actually getting better at the game, or whether their score keeps going up because of the new scoring methods.

Other reviewers have noted that Dorfromantik suffers heavily from Alpha or Dominant Player Syndrome—that is, when one player in a cooperative game makes all the decisions for the group. If that’s the case for you and your group: play it solo for an easy fix. Though the solo player doesn’t have the advantage of multiple player’s perspectives, examining the board, the resulting countryside is a design of their own making.

Comments